Analogue Photography: Point, Shoot, Develop - A Brief History

Here at Fred Aldous, we work hard to preserve the magic and historic importance of analogue photography which is why you will find that we stock cameras and darkroom supplies. The history of photography is fascinating; spanning continents, almost a 1000 years and is the meeting of scientific and technological inventions. We look at this incredible history and find out a bit more about the minds who made it happen.

Darkroom at Photofusion, London

Darkroom at Photofusion, London Experiments With Light

We begin our exploration of analogue photography with the invention of the pinhole camera and Camera Obscura. Ibn al-Haytham, a physicist and philosopher from Iraq, had been studying Optics and vision when he created the first pinhole camera in 1021 AD to test his theories. Although Ibn al-Haytham is the creator of the first pinhole camera, the founder of Mohism, Mo-ti, is credited with the first mention of the principles of a pinhole camera back in 400 BC.

Ibn al-Haytham's Sketch of the Human Optical System.

Ibn al-Haytham's Sketch of the Human Optical System.

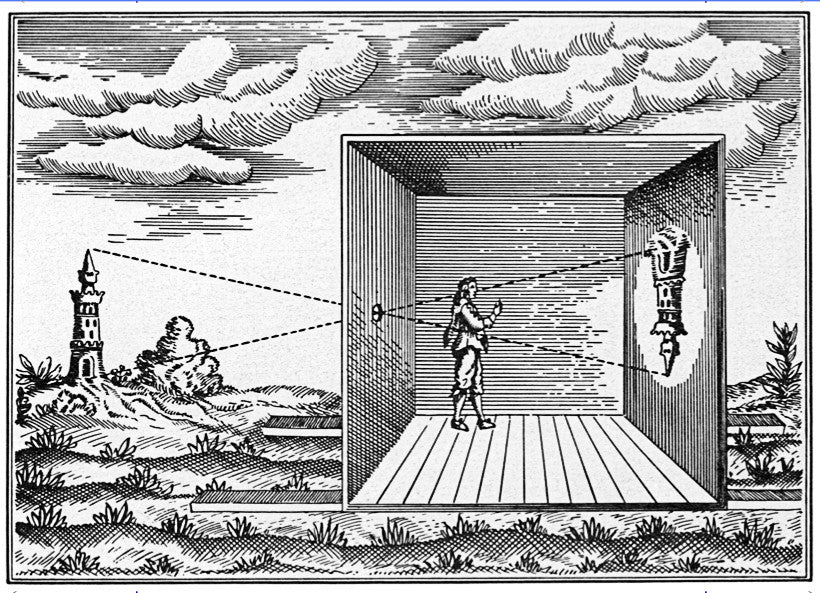

In the early history of the Camera Obscura, it was used for scientific observation, from understanding the human eye to observing solar eclipses safely, but it has also been speculated that 17th Century masters such as Vermeer used the device to produce their highly detailed paintings. The Camera Obscura is an optical device, usually a box or a room, with a hole on one side; as light passes through the hole it projects an inverted image of what is outside onto the opposite wall. Mirrors can be used to project the image the right way round and lenses are used to make a sharper image.

17th Century Illustration of a Camera Obscura

17th Century Illustration of a Camera Obscura

The Development of Chemical Photography

Another key point in the history of photography was the observation that certain chemicals were light sensitive and will be visibly altered when exposed to light. Albert Magnus discovered Silver Nitrate in the 13th Century, but it wasn't until the 18th Century that light-sensitive chemicals were used to capture an image from a camera. Four men from England and France are credited with taking the first photographs and revolutionising the process for commercial use; Thomas Wedgwood, Henry Fox Talbot, Nicéphore Niépce and Louis Daguerre. Wedgewood used paper or white pieces of leather painted with silver nitrate in direct sunlight or inside a Camera Obscura in an attempt to capture a permanent image. Although he had success in capturing shadow images in around 1790, these images eventually darkened and disappeared as he had no way of fixing them.

More successfully, Niépce, in 1816 managed to capture images using a small camera and paper coated with Silver Chloride, however, the photograph he captured was a negative rather than a positive image. Again, how the image was preserved also presented a problem. However in 1826 Niépce found success and produced the first permanent photographic image from a camera, View From The Window at Le Gras.

View from the Window at Le Gras - Nicéphore Niépce

View from the Window at Le Gras - Nicéphore Niépce

The process to capture this image has been said to take eight hours, but more contemporary research has discovered it is likely to have taken days. Niépce used a Camera Obscura and a piece of pewter coated with Bitumen of Judea to take the photograph. The areas that were most brightly light caused the Bitumen to harden and the darker areas remained soluble and were washed away with lavender oil and petroleum. After his success with Bitumen, Niépce began working with Daguerre, perhaps the most famous of the three photographic pioneers and the inventor of Daguerreotypes.

Boulevard du Temple, a daguerreotype made by Louis Daguerre in 1838

Boulevard du Temple, a daguerreotype made by Louis Daguerre in 1838

After Niépce's death, Daguerre explored the light-sensitive potential of Silver Salts and in 1839, the Daguerreotype was the first commercial type of photography introduced across the world. A Daguerreotype was produced on a highly polished sheet of silver-plated copper which was made light sensitive by exposure to halogen fumes. Once the image had been exposed onto the plate (which could take seconds or minutes depending on the lighting conditions) it was then fixed and sealed, behind a glass plate. Shortly after Daguerre's invention, Fox Talbot went on to develop the foundations of photography; developing, fixing and printing. Unlike Daguerreotypes, Fox Talbot's method enabled numerous copies of the image to be printed.

Daguerreotype of Louis Daguerre in 1844

Daguerreotype of Louis Daguerre in 1844

After the public announcement of the Daguerreotype, there was a flurry of inventions and many new photographic processes were established. The invention of the Wet Plate Collodion process in 1851 by Frederick Scott Archer replaced the use of Daguerreotypes but it wasn't long before another innovative process, Dry Plate, conceived by Richard Leach Maddox in 1871, became the chosen method for photography. Once the process had been refined by Charles Harper Bennett, Dry Plate photography revolutionised how to and who could take photographs.

A dry plate photograph - photographer unknown

Mass Market Photography

George Eastman was an American inventor and the founder of the Eastman Kodak Company. His first camera, the 'Kodak' went on sale in 1888 and by 1889 he was manufacturing celluloid film (previously, the film was made from paper). Eastman's most famous achievement in mass-market photography was the Brownie, which went into production in 1900. The camera was hugely popular and models of the camera remained on sale until the 1960's. By 1915 35mm film was being produced and it is this format which is perhaps most popular with the amateur photographer today.

Analogue Photography Today

After the advent of digital photography there was a huge decline in the use of film in amateur photography and sadly darkrooms and previously successful film manufacturers began to close. Polaroid and Kodak filed for bankruptcy in the mid 2000's and darkrooms in universities were slim lined to make room for editing suites or removed altogether. However, it's not all doom and gloom, as we've seen renewed interest in analogue photography over the last few years. We hope it continues to grow because there is a certain charm to shooting on film that you just don't get with digital. Each shot counts and there is nothing more exciting than receiving your prints back from the developers or witnessing the magic as your images appear in the darkroom.

Leave a comment